Introduction

The Indian GAAR (Chapter X-A of the Income-tax Act, 1961 [‘the Act’])) was introduced in the Finance Act 2012 and came into effect on April 1, 2017. Prior to the introduction of GAAR, Indian courts have dealt with tax avoidance cases and have developed principals, also referred to as judicial doctrine to combat arrangements that were entered into with the intention to avoid taxation (JAAR: Judicial Anti-Avoidance Rules)[1]. Even prior to the celebrated Vodafone case, Indian Courts have dealt with the vexed question of tax-avoidance in a catena of judgements articulating various principles, including ‘substance over form’, ‘lifting the corporate veil’, tax evasive structures opposed to public policy[2]. Equally, with successive judgements evolved a set of legislative measures to introduce a host of Specific Anti-Avoidance measures in the law[3].

There have been very few GAAR cases so far in India.[4] In these case law, GAAR claims have been rejected on procedural[5] and revenue threshold grounds[6]. However, recently India’s Telangana High Court—in an important decision—decided on a writ challenge against the show-cause notice that invoked GAAR proceedings[7]. The Court upheld the invocation of GAAR and its overriding effect over Specific Anti-Avoidance Rules (SAAR). This paper is a critical analysis of the decision.

Recapitulation of the Facts & Issue

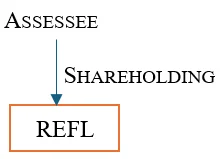

The assessee held shares in Ramky Estate and Farms Limited [‘REFL’] valued at Rs 115 per share. REFL issued bonus shares to its shareholders in the ratio of 5:1; as a result, the face value of each share got reduced to 1/6th of its value. After a short period of 10 days, the assessee sold around 5 lakhs shares to another firm that resulted in a business loss of INR 462 crores. The assessee set-off this short term capital loss against a long term capital gain. Furthermore, the ledger of REFL reflected a writing off of an inter corporate deposit to the tune of INR 288.50 crores.

The Revenue treated this transaction as an impermissible avoidance arrangement[8] contending that the motive of the transactions was to claim business loss against taxable gains. As a result, a show-cause notice was issued to the assessee initiating GAAR proceedings under section 144BA of the Act.

The ground for the writ was that the initiation and continuation of the GAAR proceedings was illegal, arbitrary and ultra vires the Act, lacking in subject jurisdiction.

Arguments of the Assessee

- Counsel for the assessee argued that the transactions in question are covered under Chapter X of the Act that constitute the SAAR[9].

- Section 94(8) of the Act was specifically incorporated as an anti-avoidance provision in relation to bonus stripping[10] with respect to the purchase and sale of units of mutual funds.

- Counsel argued that section 94(8) of the Act never had the intention of including shares and security within the scope of bonus stripping; if the Parliament would have intended the same, they would have included it within the section.

- Hence, as SAAR was applicable to the present case, the assessee argued that GAAR was not applicable. Reliance was placed on the Shome Committee report and the principal of harmonious interpretation.

Arguments of the Revenue

- The Revenue argued that there was no patent illegality on the grounds of jurisdiction to entertain the writ.

- Further, it argued that GAAR proceedings under Chapter X-A of the Act were invoked as the transactions lacked business purpose and commercial substance.

Decision of the High Court

A brief summary of the decision of the High Court is as follows:

First, the Court noted that generally where the general provision of law is in force, the special provision is subsequently enacted and in such a case the special would supersede the general law. However, in the present case, it was the opposite and hence GAAR prevails[11]. It is pertinent to note that the Court has not gone into the merits on the application of GAAR. It has answered a limited question on the application of GAAR in view of the non-obstante clause.

Secondly, the Court highlighted that Chapter X-A begins with a non-obstante clause; thus, chapter X-A of the Act gets an overriding effect over and above anything under the Act[12]. Further, it looked at section 100 of the Act[13] to discern the legislative intention that the GAAR provisions should act as an all-encompassing safety net[14].

Thirdly, it held that the assessee’s assertion that section 94(8) of Act is inapplicable for shares contradicts the argument that SAAR should prevail over GAAR[15].

Thereafter, it rejected the Shome Committee report[16] (regarding prevalence of SAAR over GAAR) as it referred to international agreements, not domestic cases[17]. On the contrary, it referred to the CBDT circular[18] that clarifies that both GAAR and SAAR would be applied depending upon the specifics of each case[19].

Lastly, it noted that JAAR placed the burden of proof on the revenue; on the contrary, as per section 96(2) of the Act, the burden is on the taxpayer[20].

Furthermore, the court held that the Revenue had persuasively shown clear and convincing evidence to suggest that the entire arrangement constituted an impermissible avoidance arrangement[21] and that the Petitioner hadn’t provided persuasive proof to counter the claim[22].

Analysis

As Mr. Pramod Kumar (Former President, Income-tax Appellate Tribunal) puts it, this was not a simple case of bonus stripping but a complex-web of tax driven transactions[23]—moreover, not a case of units of a mutual fund—hence, the decision that SAAR doesn’t cover the case appears good in law. Furthermore, we are of the view that there was no patent illegality to sustain the writ.

Assuming SAAR applies, the language of the statute (Chapter X-A of the Act) is such that GAAR will override SAAR for reasons discussed below.

In the authoritative work on Interpretation of Statutes by Justice G.P. Singh, he enunciates (based on case law[24]) that where the intention to supersede the special law is clearly evinced, the later general law will prevail over the special law.[25] The non-obstante clause in the later general law can be given overriding effect over the special law when there is a clear inconsistency between the two laws[26]. In the present case, the presence of the ‘non obstante’ clause in Chapter X-A of Act, which is in the later law, indicates that the GAAR will override SAAR (considering the inconsistency between GAAR and SAAR), assuming SAAR is applicable. GAAR does not preclude bonus stripping in case of shares from the scope of anti-avoidance measures, but section 94(8) of the Act is argued to preclude it.

In the view of the authors, neither SAAR (section 94(8) of the Act) nor GAAR precludes bonus stripping in relation to shares from the scope of GAAR. In fact, there is nothing in section 94(8) of the Act or the relevant Explanatory Memorandum precluding bonus stripping of shares from the scope of anti-avoidance measures. The absence of it only means that there is no specific provision to cover it. Its preclusion from GAAR cannot be assumed or inferred.

However, the argument of the assessee in this case has ignited a debate on GAAR v. SAAR in India. As a matter of fact, the Shome Committee constituted by the Ministry of Finance to give recommendations on the implementation of GAAR specifically recommended that if SAAR provision is applicable, GAAR should not apply[27]. Regrettably, the recommendation of the expert committee did not find its way in the final law, neither was this aspect clarified by way of an administrative direction.

The issue of GAAR v. SAAR has divergent rulings and practices across the world[28]. In Canada, where the Revenue Authorities have challenged taxpayers’ transactions on both the basis of SAAR and GAAR, the Courts have generally applied the more specific SAAR[29]. However, in a recent ruling in Deans Knight[30], the Supreme Court of Canada applied GAAR where SAAR existed[31]. The Court clarified that the GAAR applies not only to unforeseen tax strategies but also to tax strategies for which Parliament has already drafted provisions[32]. This indicates an increasing judicial trend towards the application of GAAR over SAAR. In China, the China State Administration of Taxation has reaffirmed that only when tax benefits arising from arrangements cannot be eliminated through the application of SAAR that the tax authorities can initiate GAAR investigation[33]. In Poland, GAAR will not apply if SAAR applies[34]. In Germany if SAAR applies, GAAR cannot be applied cumulatively[35].

In the Statement of the Indian Finance Minister dated January 14, 2013, he had clarified[36] that where both GAAR and SAAR are in force only one will be applicable and guidelines will be made in this regard. This in the opinion of the authors was the middle path that the then Finance Minister decided to take, given the expert committee’s recommendations. Further, no such guidelines have been released by the Department of Revenue and it has been left to judicial interpretation. From the principles discussed above, it is our view that the application of GAAR or SAAR in a domestic context (as per Indian law) should clearly be decided on a case-by-case basis based on the language, parliament’s intent and the timing of the statutory provisions.

It will be interesting to see how the Indian courts may interpret GAAR v. SAAR in an international context. The CBDT circular[37] discussed above mentions that anti-abuse rules in tax treaties may not be sufficient to address tax avoidance strategies and the domestic anti-avoidance rules become applicable. This guidance suggests that it was the intention of the law makers to retain an empowerment to invoke GAAR in specified situations.

It is our view that unless the tax treaties specifically allow the overriding of domestic anti-avoidance provisions over the tax treaties—as in the cases of India’s tax treaties with Bhutan, Kenya and Malaysia—GAAR should not apply if the case satisfies the Principal Purpose Test/Limitation of Benefits in the tax treaty.

In line with this view, in an excellent recent decision by the Delhi High Court in Tiger Global,[38] the Court denied the application of GAAR where the treaty grandfathered acquisitions prior to a specified period thereby holding that GAAR would not override the tax treaty. In summary, there clearly seems to be divergence in the treatment of GAAR v. SAAR vis-à-vis international transactions as opposed to domestic transactions. In our view, this reasoning is in view of the application of the principle of pacta sunt servanda in the international context. But, GAAR v. SAAR in a domestic context would depend—as discussed above—on a case by case basis.

Conclusion

The decision of the Telangana High Court has been challenged before the Supreme Court. It will be interesting to see what the Supreme Court decides, if it grants leave (allows) in the Special Leave Petition.