“When digital transformation is done right, it’s like a caterpillar turning into a butterfly, but when done wrong, all you have is a really fast caterpillar.” This quote by George Westerman, from an MIT Sloan Initiative on the Digital Economy, was in the context of digital transformation not being a switch one can turn on with the right amount of investment—there are ways to do it correctly and ways to do it otherwise. It seems apt to juxtapose this in the context of India’s digital tax levy, which increasingly seems to be taking the shape of a fast caterpillar.

India introduced its digital tax levy in 2016, based on a report by an eight-member committee, to evaluate taxation on digitized business otherwise remaining untaxed due to traditional treaty and non-treaty rules. The eight member committee comprised of five members from the tax administration, two professionals, and an industry representative. In what appears to be an irony, the committee on “taxation of e-commerce,” recommended that what is normally understood as e-commerce or digital commerce need not necessarily attract the digital tax (termed as “equalization levy” in India). The committee went on to specify certain “non-e-commerce” activities, which should be within the scope of the levy and recommended a rate of 6% on gross revenues. The levy was introduced in the Finance Act of 2016 with limited scope to levy tax on business-to-business digital advertising. The incidence of levy was on the resident Indian service recipient. In accordance with the committee’s recommendations, the scope of the levy was significantly enhanced in the Finance Act of 2020, at which point the rate was amended to 2% of gross consideration, although the incidence was shifted to the non-resident e-commerce service provider. There were significant anomalies around the expanded scope leading to a flurry of reaction from digital players and an adverse finding report from the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR 301 report).

In the period between 2016 and expanded scope in 2020, several jurisdictions introduced their own version of digital services tax (DST), with India emerging as the frontrunner of this unilateral tax immediately after the Action 1 report of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Digital players have expressed disillusion over such unilateral levies by countries.

The OECD is seeking to achieve consensus on taxing digital businesses under Action Plan 1 of its OECD/G20 BEPS Inclusive Framework initiative, which has 137 nations as participants. While, the OECD’s effort is laudable, it is unclear when the consensus will see the light of day, and more importantly, Action Plan 1 is not a minimum standard, meaning even if a consensus is arrived at, nations could choose to not adopt it or adopt with varying degrees of consistency.

The global Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 has compelled governments across the world to introduce a slew of measures to mobilize tax revenues for social and health considerations. India’s 2020 budget, which was passed by the parliament on arrival of the Covid lockdown was no exception. The extenuating circumstances did not afford adequate time to debate the expansive levy, taking digital players by surprise. This clearly lead to anomalies in the interpretation of the law, which seems to have been corrected by way of 2021 proposals. In India’s otherwise widely appreciated 2021 Budget proposals, the proposal to modify India’s equalization levy has been the proverbial thorn in the rose, given that e-commerce players view it as further expanding the scope of the levy under the garb of a rationalization measure. A welcome measure is apart from proposing clarifications on scope of the levy, the budget has also clarified that income treated as royalty or fees for technical services shall be outside the ambit of the levy.

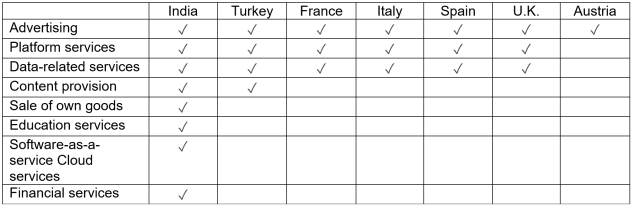

When India expanded the scope of its equalization levy in 2020, the government received several representations from stakeholders, seeking clarity on the scope and applicability of the levy. The scope was viewed as expansive enough to cover all kinds of digital transactions on sale of goods or provision of services supplied to Indian residents and included non-residents using an Indian internet protocol (IP) address. It specifically covered transactions between non-residents and e-commerce operators where advertisements were targeted at Indian residents or customers using an Indian IP address; and sale of data collected from Indian residents or customers using an Indian IP address. Unlike the 2016 levy, the 2020 levy thrust the compliance burden on the non-resident e-commerce operator. With the 2020 expansion, India’s equalization levy went beyond the contors of digital taxes applicable in other jurisdictions, resulting in far reaching impact for players in the digital industry. In the USTR 301 report published in January 2021, the USTR found the levy to have the broadest scope in comparison with other DSTs and disapproved of the same as discriminatory, unreasonable, and restricting U.S. commerce. The report laid out a chart comparing India’s levy with that of other countries—which has been reproduced below.

The USTR 301 findings had taken a shot at estimating the number of taxpayers who may be covered under the 2020 equalization levy to conclude that there were about 119 companies that may be covered of which 86 were U.S.-headquatered companies. It appears that the 2021 budget proposals further expand the scope of the levy to propose that online activities i.e., (1) the acceptance of and offer for sale; (2) placing a purchase order; (3) acceptance of a purchase order; (4) payment of consideration; and (5) supply of goods or provision of services, partly or wholly, shall be included under “online sale of goods” and “online provision of services.” The 2021 budget has clarified that the equalization levy will be imposed on considerations received/receivable from e-commerce supply or services, irrespective of whether the e-commerce operator owns the goods; or whether services are provided or facilitated by the e-commerce operator. This would imply that that an e-commerce operator which is operating as a market place (neither purchasing nor selling) would be liable to pay equalization levy on its entire transaction value, and not just on the commission it receives. In addition there is a proposal that leads to substantial questions with respect to applicability of the levy where even one leg of a transaction is concluded digitally via the e-commerce platform—it is no longer necessary for a transaction to be conducted online wholly or substantially. In what was a widely criticized amendment in 2020, the 2021 proposed amendments have added fuel to the fire raising questions on the strictest form of nexus principles being applied to trace the source of income.

The Department of Revenue would do well to engage with stakeholders before the budget proposals are enshrined in the Finance Act. It would be helpful if the government addresses the ambiguities in the broadend scope of the levy in light of the changes. India’s ambitious digital agenda, which is an integral part of India’s public policy goal is a double-edged sword. On one hand it attracts domestic and foreign investment to capitalize on the opportunity, and on the other hand, the tax administration desires to tax a portion of growing e-commerce. India’s potential on domestic e-commerce has only flourished in Covid times, leading several technology giants to reengineer their operations either with enhancement of onshore presence or by way of making foreign direct investment (FDI) in this burgeoning growth segment. India’s leading domestic e-commerce player Jio raised a record FDI of around $20 billion over ten corporate funding rounds, spanning a mere three months, in the midst of nationwide Covid lockdown. Foreign investors included technology giants such as Facebook, Google, Intel, and sovereign wealth funds amongst others. The growing domestic e-commerce market, coupled with onshore presence of MNC giants shall automatically lead to a shrinking pie of non-resident e-commerce players.

Research has shown that expansion of e-commerce has benefited small, micro, and medium enterprises reach customers, hitherto not accessible due to inadequate logistics, infrastructure, and funding needs—a requirement fulfilled by the market place e-commerce model, as is presently permitted under the FDI rules.

In this situation, to impose onerous compliance or regulations which are ambiguous, may have adverse long-term consequences. A case in point is non-appealibility of tax administrations order on e-commerce operators. In our view, a calibrated approach is needed, which amongst others should address the ambiguities in the law, review the strict nexus principle in light of digital taxes in other jurisdictions, and provide a mechanism to appeal against the order.

The OECD debate on digital taxation, is likely to be concluded in 2021 and the question is should India have waited for a year? Recent news articles suggest ongoing discussions between the Ministry of Commerce in India and its counter parts in the new U.S. administration to seek resolutions to wider trade and tariff issues are proceeding well. India’s commerce secretary, in a recent statement said the sticky points have been addressed and the “status is very good on that deal”…India and the U.S. are natural allies and strategic trade partners with both countries standing to benefit immensely by collaborating with each other. While India’s equalization levy, which is not discriminatory in as much as its applies equally to all non-resident digital players (resident digital players are subject to alternate domestic taxes), the ambiguity around the scope and the manner of clarification leaves a lot to be desired.

To summarize, given the Indian government’s larger public policy thrust on digitalization, and the government’s stated objective of making the Indian tax regime transparent and efficient, a compelling case of stakeholder consultation is made. In the government’s exuberance to plug loopholes on the applicability of its equalization levy, while it could hastily realize its taxing rights as a market jurisdiction, the levy may end up becoming a fast caterpillar instead of a butterfly.

Mukesh Butani and Seema Kejriwal are partners at BMR Legal. The authors acknolwedge the contribution of Sumeir Ahuja, associate at BMR Legal.